How does access to electricity affect people’s lives?

Free electricity connections in rural South African households changed home production technologies and induced more women to work in the market

There has been considerable progress in the last two decades towards the UN’s 7th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG7): “access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all by 2030”. Since 2000, the share of people with access to electricity in least developed countries has more than doubled.1 What impacts can we expect this type of energy access to have on people’s lives?

Work in South Africa offers one example of what can happen when rural households get new access to free electricity connections and low-cost power (Dinkelman 2011). My study examines how a large-scale, government-financed programme to electrify rural households in South Africa changed the environment of work at home as well as in the market, over a five-year period.

In the mid-1990s in South Africa, the national power utility (Eskom) committed to addressing apartheid-era infrastructure deficits by financing new electricity connections for 300,000 households every year. These new connections were provided to households for free, and power could be purchased at very low marginal costs. Eskom largely succeeded in meeting their connection targets. Household electrification rates climbed from 35% of all households in 1990 to 84% in 2011 (StatsSA, 2012).

Once a community was chosen to be connected to the grid, all existing households in the community were connected with pay-as-you-go meters. Using census data from the mid-1990s and early 2000s, and focusing on about 1,800 of the most underserved rural areas (ex-homelands), the author tracked community-level economic outcomes over time as rural communities became connected to the grid.

A key challenge in the analysis was to establish that changes in outcomes in connected versus unconnected communities were caused by new connections to the grid and not by some other factors that were changing simultaneously. Luckily, the context of electricity rollout allowed the author to exploit a programme feature that was unlikely to be related to other economic trends: Eskom had clear incentives to connect communities that were the least costly to electrify.

One of the key factors driving Eskom’s cost of connecting a household at the time was land gradient. Flatter communities were cheaper to electrify, due to engineering constraints. Capitalising on this insight, I estimated the effect of rural household electrification by comparing outcomes across communities that differed only in their land gradient. Flatter communities, while more likely to be connected to the grid, were otherwise similar to non-connected communities.

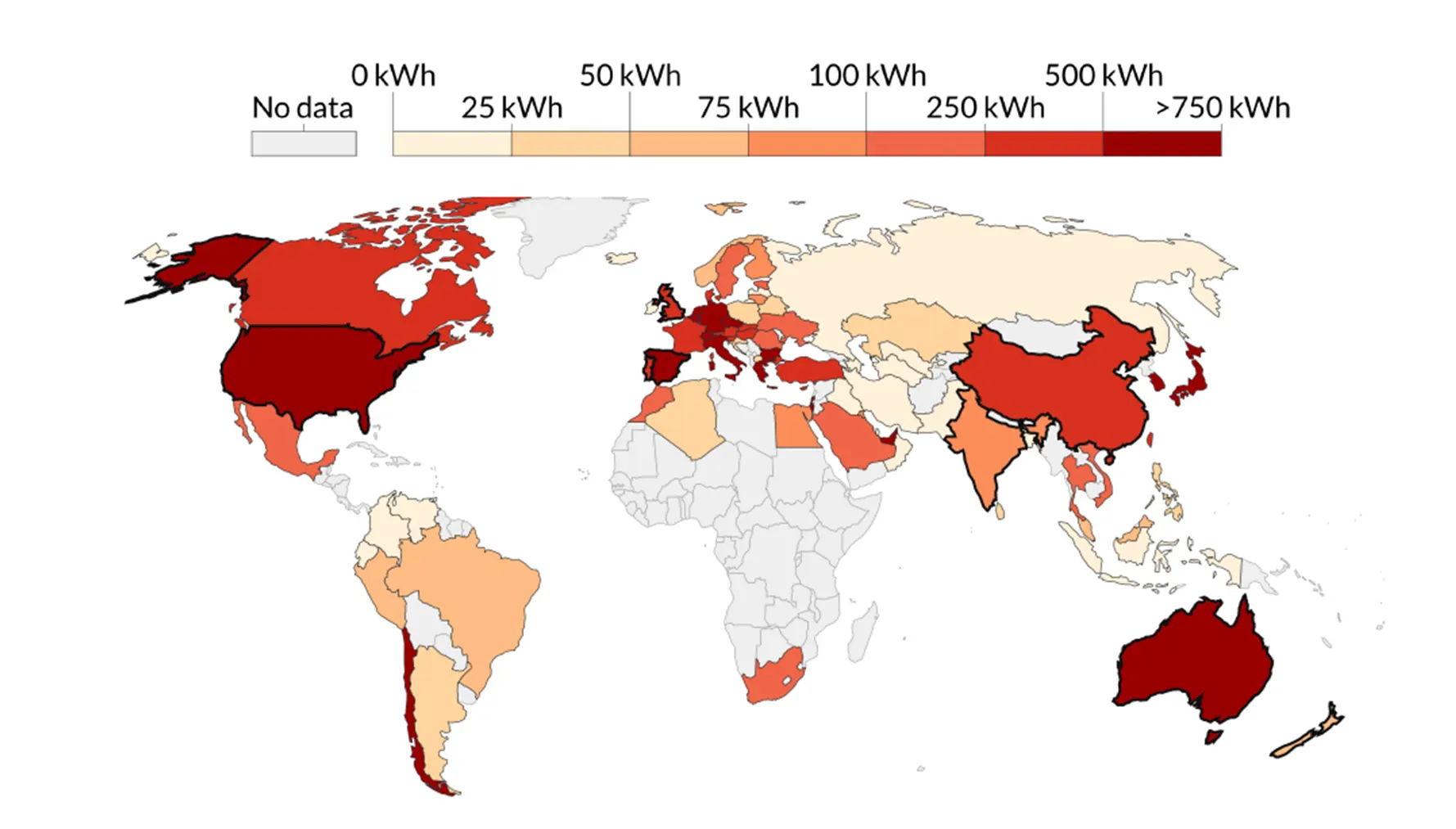

In the map we see differences in per capita energy use; this is inclusive of all dimensions of energy (electricity plus transport and heating). There are several important points to note. Firstly, there are large inequalities in energy consumption between countries. The average US citizen still consumes more than ten times the energy of the… Continue reading Per capita energy consumption varies more than 10-fold across the world

December 1, 2022 Read More